-40%

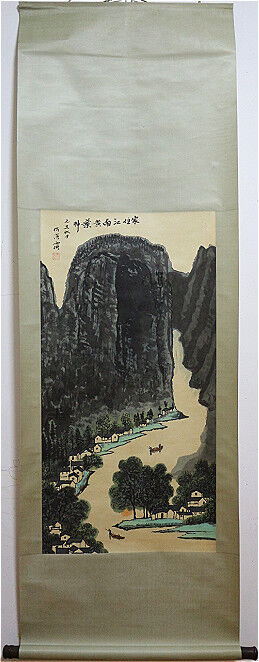

Chinese painting brochure Liaoning Museum 'Song Dynasty bird and-flower painting

$ 89.23

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

Culture of the Song dynastyThe Song dynasty (960–1279 AD) was a culturally rich and sophisticated age for China. There was blossoming of and advancements in the visual arts, music, literature, and philosophy. Officials of the ruling bureaucracy, who underwent a strict and extensive examination process, reached new heights of education in Chinese society, while general Chinese culture was enhanced by widespread printing, growing literacy, and various arts.

Appreciation of art among the gentry class flourished during the Song dynasty, especially in regard to paintings, which is an art practiced by many. Trends in painting styles amongst the gentry notably shifted from the Northern (960–1127) to Southern Song (1127–1279) periods, influenced in part by the gradual embrace of the Neo-Confucian political ideology at court.

People in urban areas enjoyed theatrical drama on stage, restaurants that catered to a variety of regional cooking, lavish clothing and apparel sold in the markets, while both urban and rural people engaged in seasonal festivities and religious holidays.

Chinese painting during the Song dynasty reached a new level of sophistication with further development of landscape painting. The shan shui style painting—"shan" meaning mountain, and "shui" meaning river—became prominent features in Chinese landscape art. The emphasis laid upon landscape painting in the Song period was grounded in Chinese philosophy; Taoism stressed that humans were but tiny specks amongst vast and greater cosmos, while Neo-Confucianist writers often pursued the discovery of patterns and principles that they believed caused all social and natural phenomena. The making of glazed and translucent porcelain and celadon wares with complex use of enamels was also developed further during the Song period. Longquan celadon wares were particularly popular in the Song period. Black and red lacquerwares of the Song period featured beautifully carved artwork of miniature nature scenes, landscapes, or simple decorative motifs. However, even though intricate bronze-casting, ceramics and lacquerware, jade carving, sculpture, architecture, and the painting of portraits and closely viewed objects like birds on branches were held in high esteem by the Song Chinese, landscape painting was paramount. By the beginning of the Song dynasty a distinctive landscape style had emerged. Artists mastered the formula of creating intricate and realistic scenes placed in the foreground, while the background retained qualities of vast and infinite space. Distant mountain peaks rise out of high clouds and mist, while streaming rivers run from afar into the foreground.

There was a significant difference in painting trends between the Northern Song period (960–1127) and Southern Song period (1127–1279). The paintings of Northern Song officials were influenced by their political ideals of bringing order to the world and tackling the largest issues affecting the whole of their society, hence their paintings often depicted huge, sweeping landscapes.[5] On the other hand, Southern Song officials were more interested in reforming society from the bottom up and on a much smaller scale, a method they believed had a better chance for eventual success.[5] Hence, their paintings often focused on smaller, visually closer, and more intimate scenes, while the background was often depicted as bereft of detail as a realm without substance or concern for the artist or viewer.[5] This change in attitude from one era to the next stemmed largely from the rising influence of Neo-Confucian philosophy. Adherents to Neo-Confucianism focused on reforming society from the bottom up, not the top down, which can be seen in their efforts to promote small private academies during the Southern Song instead of the large state-controlled academies seen in the Northern Song era.

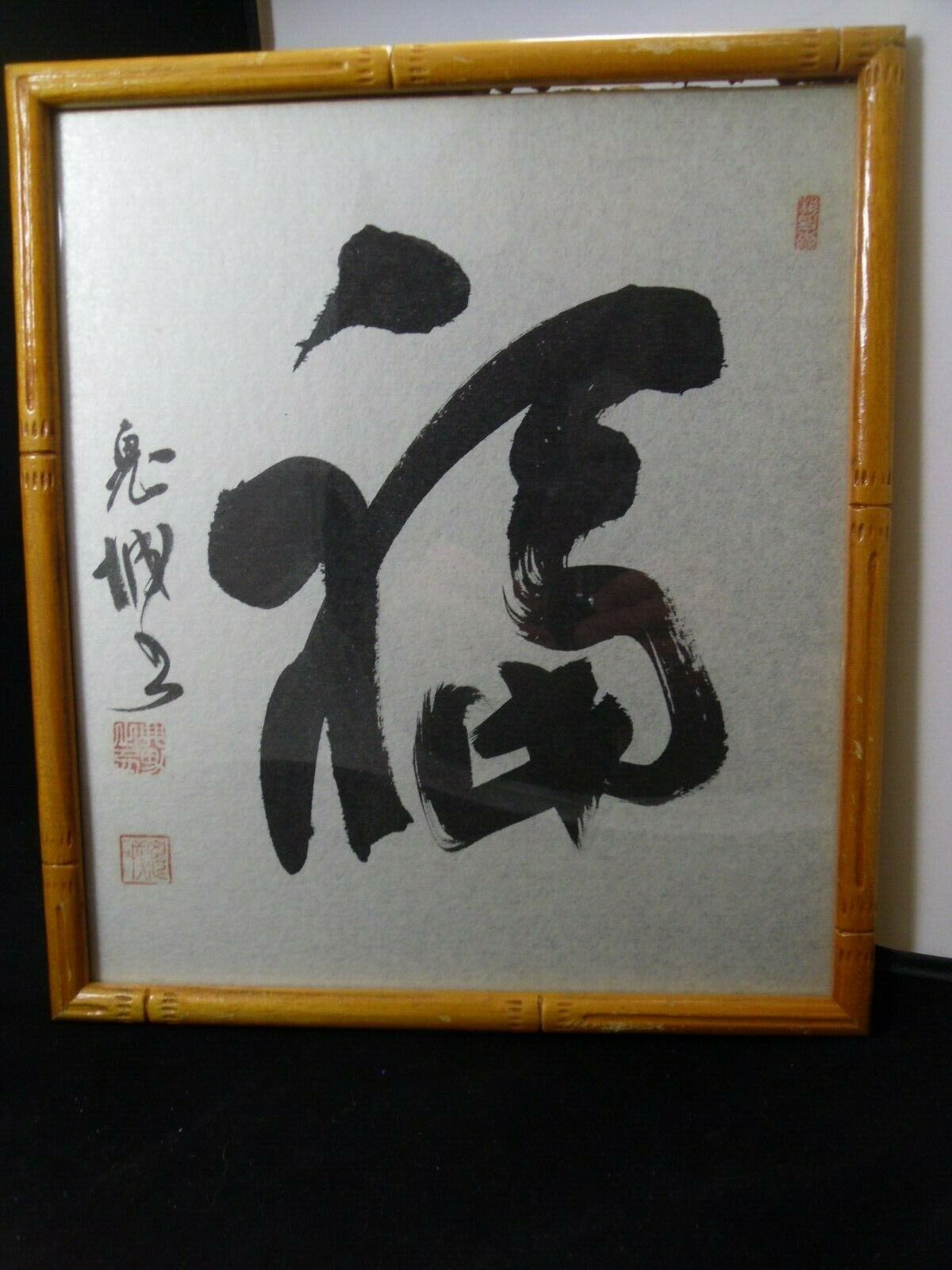

Ever since the Southern and Northern Dynasties (420–589), painting had become an art of high sophistication that was associated with the gentry class as one of their main artistic pastimes, the others being calligraphy and poetry. During the Song dynasty there were avid art collectors that would often meet in groups to discuss their own paintings, as well as rate those of their colleagues and friends. The poet and statesman Su Shi (1037–1101) and his accomplice Mi Fu (1051–1107) often partook in these affairs, borrowing art pieces to study and copy, or if they really admired a piece then an exchange was often proposed.[8] The small round paintings popular in the Southern Song were often collected into albums as poets would write poems along the side to match the theme and mood of the painting.

Although they were avid art collectors, some Song scholars did not readily appreciate artworks commissioned by those painters found at shops or common marketplaces, and some of the scholars even criticized artists from renowned schools and academies. Anthony J. Barbieri-Low, a Professor of Early Chinese History at the University of California, Santa Barbara, points out that Song scholars' appreciation of art created by their peers was not extended to those who made a living simply as professional artists:

During the Northern Song (960–1126 CE), a new class of scholar-artists emerged who did not possess the tromp l'oiel skills of the academy painters nor even the proficiency of common marketplace painters. The literati's painting was simpler and at times quite unschooled, yet they would criticize these other two groups as mere professionals, since they relied on paid commissions for their livelihood and did not paint merely for enjoyment or self-expression. The scholar-artists considered that painters who concentrated on realistic depictions, who employed a colorful palette, or, worst of all, who accepted monetary payment for their work were no better than butchers or tinkers in the marketplace. They were not to be considered real artists.

However, during the Song period, there were many acclaimed court painters and they were highly esteemed by emperors and the royal family. One of the greatest landscape painters given patronage by the Song court was Zhang Zeduan (1085–1145), who painted the original Along the River During Qingming Festival scroll, one of the most well-known masterpieces of Chinese visual art. Emperor Gaozong of Song (1127–1162) once commissioned an art project of numerous paintings for the Eighteen Songs of a Nomad Flute, based on the woman poet Cai Wenji (177

–

250 AD) of the earlier Han dynasty. The Southern Song dynasty court painters included Zhao Mengjian (

趙孟堅

, c.1199

–

1264), a member of the Imperial family, known for popularising the Three Friends of Winter.

During the Song period Buddhism saw a small revival since its persecution during the Tang dynasty. This could be seen in the continued construction of sculpture artwork at the Dazu Rock Carvings in Sichuan province. Similar in design to the sculptures at Dazu, the Song temple at Mingshan in Anyue, Sichuan province features a wealth of Song era Buddhist sculptures, including the Buddha and deities clad in lavish imperial and monastic robes

。

五代~北宋時代には、荊浩、董源、巨然、李成、范寛、郭熙など、その後千年間古典とされた山水画専門または山水画で有名な巨匠達が輩出し、従来、絵画の本流だった人物画をしのぐ状況となった。文人官僚が鑑賞する絵画として山水画が賞揚され、当時の指導的文化人たちが批評を書き、画家の社会的地位が上昇し、名画は高価で売買されていた。宮廷でエリートが集まる翰林院の壁画が山水画であったのは象徴的である。唐時代以前の宮殿の壁画は、聖人君子、功臣たちの肖像、教訓的逸話など人物画が中心であったからである。作品としては、范寛『渓山行旅図』(台北 国立故宮博物院)、郭熙『早春図』(台北

国立故宮博物院)、巨然『渓山蘭若図』

(Cleveland Museum of Arts)

がある。北宋時代の山水画は巨大な自然と微小な人事の対照を強調した作品が多い。南宋時代には、絵の中の人物が山水を鑑賞するという設定の作品が多くなり、また山岳を画面の一部にして空白部分を多くとる作品がでてくる。馬遠、夏圭が有名画家である。

14

世紀、元時代、「専門画家ではない文人によって制作される山水画」という理念が成長した。元末四大家とされる、黄公望、呉鎮、倪雲林、王蒙の四画家は、それぞれ特色のある様式を確立しただけではなく、「非職業的画家、アマチュア画家が学ぶべき山水画の様式」を現実の作品として創造し、後世に絶大な影響を与えた。特に倪雲林は「心象風景としての山水画」を明確に提示した。紙本水墨淡彩という、技術的に容易で、アマチュアにも近づき易い手法も確立した。

On Mar-17-17 at 01:36:32 PDT, seller added the following information:

Track Page Views With

Auctiva's FREE Counter